Today is the 20 year anniversary of my mother, Diane’s, death from a brain tumor at the age of 55. Sometimes it feels like she was never here. Except for myself, my sister, and my mother’s siblings, sometimes it feels like no one else ever knew she was alive. Except for her obituary, there is almost no evidence of her on the internet. She doesn’t even have a gravestone marker. Her ashes were spread in a beautiful, but somewhat inaccessible place–the Maroon Bells of Colorado. She never met my children. They only vaguely understand who she was, despite my attempts to share stories about her. She only met my husband (who was not my husband at the time) briefly in a sort of tension filled 5-minute meeting. At times here and there, it feels like she is a figment of my imagination, only shared with my sister.

But then I always remember the words of Eva Schloss, who was a holocaust survivor that lost her father and brother in the concentration camps. She talks about the words of her father that she always remembered and tried to always carry on:

“I promise you this. Everything you do leaves something behind; nothing gets lost. All the good you have accomplished will continue in the lives of the people you have touched. It will make a difference to someone, somewhere, sometime, and your achievements will be carried on. Everything is connected like a chain that cannot be broken.”

Erich Geiringer

And then I look around, and I see her everywhere. She is inside my head. She is in the very walls of my house. She is in my children. And despite his 81-year-old somewhat impaired mind, she is still in my dad. The chain links are connected in numerous ways. My mother was a very private woman, which has made it hard to write about her without a lot of guilt. But I also feel like I could do more to sew a tapestry of who she was, each thread may add a little link in the chains I pass down to my children.

To understand my mother, you must appreciate where she came from. She grew up in Council Bluffs, Iowa in hard circumstances, surrounded by alcoholism, domestic violence, and poverty. As the oldest child, she often felt a responsibility to take care of her younger 3 sisters and one brother. She tried to fill in gaps that her parents were unable to fill. Sometimes, when her younger sister had trouble in school, she would be called in by the principle to intervene because her parents were not available. Sometimes, when there wasn’t food in the house, she would go out to buy it with money she earned from part-time work. Sometimes, she had to intervene with social welfare offices to make sure the food stamps did not get cut off. She was always honest about her past with us. She never cherry-coated it. I would visit some of my relatives and see some of the alcoholism and dysfunction myself at times. Because she was honest with us, it helped me to realize from an early age that it was dysfunction and not how life should be. I knew early on some of the warning signs of men who were verbally and physically abusive to women, people who drank too much and how that impacted their lives, and also how blatant and abnormal racism and sexism was. By being honest with us about how it was, we had a way to interpret it and understand how it could be. It helped my sister and I to be able to set a higher standard for ourselves and to not get trapped in some of the situations we saw some family members in.

When she graduated high school, my mom tried to get out. She moved to California to live with her aunt and uncle. The plan was that she could live there and go to college for free. But alcoholism struck again. Her aunt was very ill from alcoholism and on the brink of divorce. Although I think they had the best intentions, they felt that they could not support my mother and she was sent back home. But there was no home to come back to. After graduation, my grandmother had put all of her things out in the driveway. She was not welcome home. And her dream of college was gone.

She got a job at the phone company and rented an apartment. There is where she met my father. They had met briefly before, when my mom was 13 and dated a guy in my father’s class. My dad was 6 years her senior, but had been held back twice, so didn’t graduate until he was 20. My dad was an attractive guy, though. My mom would dress up and put on make up just to take the trash out, because she would have to walk by his apartment then. Eventually, they started dating. She soon became pregnant with my sister and they married. He was 25, she was 19.

What Diane had come to learn at a young age, is that hard work could get her far. My father worked for the Union Pacific Railroad as a carman. My mother tried to find better work and applied for a job as a mailclerk at Mutual of Omaha. In a story printed a few years later in an insurance industry magazine on my mother’s “Horatio Alger story,” the man that hired her said when he asked her why she should hire her, a woman with children in the 1970, she famously said “because I am a hard worker.” He gave her the job. Diane had an almost infallible work ethic. She knew that if you show up, work hard, and do your best it can mitigate some of the effects of things like being a woman, being poor, and having only a high school education.

Some of my earliest memories of my mother were our morning routine. We got up at 6:30am, we got dressed and brushed our teeth. My dad, my sister and I would pile in our car, pull out of the garage and wait in the driveway. A few minutes later, my mother would come out in her fancy work clothes. She always wore heals, nylons, a skirt and a blouse, often a suit jacket, her nails were perfectly polished, and her dark hair done in a flip like Marlo Thomas on That Girl. She was young, probably only 25 or 26 then, and one of the few professional women we knew at that time. My dad would drop us off at our babysitter, Jo’s house, take her to work in Omaha across the river and then take himself to his job. It was just what we did. My sister and I went to school, they went to work. There was no drama about it ever. You were always supposed to be ready on time, be ready to work, be pleasant about it, and work your hardest.

My mother rose through the ranks at Mutual, and at some point, I remember a kind of breakthrough promotion. I believe she had become assistant vice president in this Mutual of Omaha subsidiary called “Mutual of Omaha Fund Management Company.” We would sometimes go with her to work on a Saturday, and she would set us up with typewriters to play with or papers to copy. One Saturday, our job was to help move her from the main floor, a sea of desks, into a small office. She showed us her new name plate that slide into its holder on the outside of the office door. She now had a little pen set that went on her desk. Two fancy gold pens that perched at an angle in their holders. She had these gold fringed miniature flags, too. One a flag of the United States, and one a white flag with the Mutual logo on it sat in a wood and brass flag holder on her desk. It all seemed very fancy to me, and I started to get that my mom was becoming an important person at work. She would eventually rise to Vice President of Operations, or maybe it was Chief Operating Officer, and her offices would get bigger and fancier as her pay climbed as well.

My father traveled a lot for the railroad for several years as a steel inspector. He would go to places like Youngstown, Ohio or Buffalo, New York or Pueblo, Colorado and inspect steel mills that the UP bought products from. Usually, he would be gone during the week, and we would pick him up at the airport on the weekends. Sometimes, he might be gone for several weeks in a row. I did not realize at first that other kids didn’t go to the airport twice a week like I did. So my mother had to manage a lot while we were little. She never made a big deal about it. But my sister and I always slept in her room with her when he was gone. At first, we would all sleep in her queen-sized bed. I was always in the middle. But as we got bigger, we traded off. One would sleep in the bed with her and the other would sleep in a sleeping bag on the floor. This went on for years, until the UP ended the inspection jobs and my dad was back to working at the railroad shops.

My mother almost always made more money than my father. At the end, it was something like 3 or 4 times as much. My father worked at the railroad for 40 years. He showed up every day, even though I know he was not really very inspired to work there. But often, his salary was what paid the day to day bills, plus his job provided our family with health insurance. Her money was used for vacations and bigger purchases. They made it work, and I don’t ever remember my father having any insecurities about this, nor do I remember my mother holding it over his head. They rarely fought, and I rarely had any feelings that the family was unstable or that they would divorce. Even when the UP closed the Omaha shops and my dad had to either quit or transfer far away, they stayed together. Knowing that it would be hard for my dad to find another job, they lived apart for 6 years, him in Pocatello, Idaho and her back in Omaha. They visited back and forth frequently, and the marriage endured.

I know that my mother’s goals for her family were largely to give us the stability she did not have. Financially, with their marriage, and otherwise, it was always extremely stable and secure. My parents rarely drank. They budgeted and planned carefully, They did not have significant money troubles and lived within their means; they did not fight much nor was there any violence in our house. I don’t think this necessarily came easily for her. She had really no role models and was never taught how to raise kids, manage money, keep out of trouble, etc. She always regretted that she did not get to go to college, and she always valued education. Not only formal education but being self-taught. She was skilled at finding mentors to guide her, and would also go to the library and read books on things she wanted to learn more about. Our house was filled with books about leadership, dressing for success, and managing money. Although she eventually made a very good salary, I do think the early years were lean and she also acquired some amount of debt that she paid off on behalf of my dad when they were first married.

Her marriage with my father was something I didn’t think too hard about as a child, but have come to understand much better as I have become an adult. Weirdly, I got more insight after she was gone and I saw my dad without her. I’m not sure I can explain this right, but this is what I have come to see.

From the time I was 11 or 12, I started to realize that my dad was not quite like any of the other dads, but I really couldn’t articulate why. I have come to believe that my father has some undiagnosed, relatively minor learning and emotional disabiiities. This is part-armchair, I admit. But partly because I am trained in special education assessment and the signs are really obvious to me now, even though as a kid I could not name what the deal was. My father came from a difficult background as well, and has always had a level of aphasia and learning disabilities, probably dyslexia. He is also a bit emotionally immature and unaware. I think this has to do with his own child hood trauma.

He is a good guy, my dad. He is hard working, too. He is very much WYSIWYG. He is not manipulative in any way. He is fun and means no harm. But he seems to have always required a relatively minor amount of actual life skills support from others to be his best self. For example, if he were to try to get a job in today’s job market, I think he would need a lot of help with the application process, filling out forms, maybe even some interview practice. Without help, I think he would struggle with the application process. But once he is set up in a job and knows what to do, he is fine. He will show up every day and do the job. But the job would need to be pretty straight forward. He was not stupid, he just had trouble with anything involving reading, spelling, procedural stuff, etc. And he is not unkind, but he needs to be told straight out what is going on around him and what other people might need. So, like, how to act in social situations and things like that.

You can see where they may have started out as two young poor kids from troubled families who didn’t know anything. But as my mother learned more and became more successful and became more sophisticated, he largely did not. I know she would get frustrated to take him to business parties and she would heavily prep him before hand and help him along at the event. You could easily see how they could have grown apart, but they didn’t really. She always provided just enough support to him so that he could be his best self. And he was always the steady workhorse that she could depend on. When no other dads were cooking, cleaning and doing laundry, My dad was. My dad would fix our hair and get us dressed when we were young. She expected it of him and he rose to her expectations. My dad was always fun and a bit adventurous. I think he brought that to her because she could be a little intense and even boring. She often would say how easy-going he was. How he was always positive and could see how “the cream always floats to the top.” They enjoyed going on vacations together. But my mom wanted to sit somewhere pretty and relax on vacation, and he wanted to go, go, go. So they managed to trade off every couple of years and balance it out.

From the time she got the diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme to the time she died was only about 10 months. In that time, she had life altering brain surgeries, radiation treatments and chemotherapy. Her functioning, including her cognitive functioning, changed rapidly in this time. Still, it was my father who was probably the tenderest with her, always there to support her, when sometimes my sister and I were at a loss with all the impending doom to come. In turn, she spent her time trying to set things up for the family she was leaving behind.

One thing she did, literally a day before brain surgery, was to set up a trust for my father. I do not know all the ins and outs of it, but I know her goal was that he not be taken advantage of by a woman (or anyone) attracted to a fairly young and good looking and relatively well off widower. She knew that he would need some help managing everything. And she also knew that he is so conflict adverse and sometimes oblivious that he might not see or be aware that he is being taken advantage of. She did not want him to be alone the rest of his life. None of us did. But she also knew that he didn’t have perhaps the skills or ability to discern who was really a sincere person. Her idea was that if she made all kinds of stipulations in the trust, that the woman who only wanted a meal ticket would be dissuaded. She thought that it would help to self-select only the women who could take care of themselves and had their own independent lives would come around. And then, he would have money to not only spend to enjoy his retirement with a companion on fun things like vacations and restaurants, but that he would also be ok if he needed long term care. He understood this and wanted this as well, and so in that way, Diane is still trying to watch out for him and make sure he is taken care of.

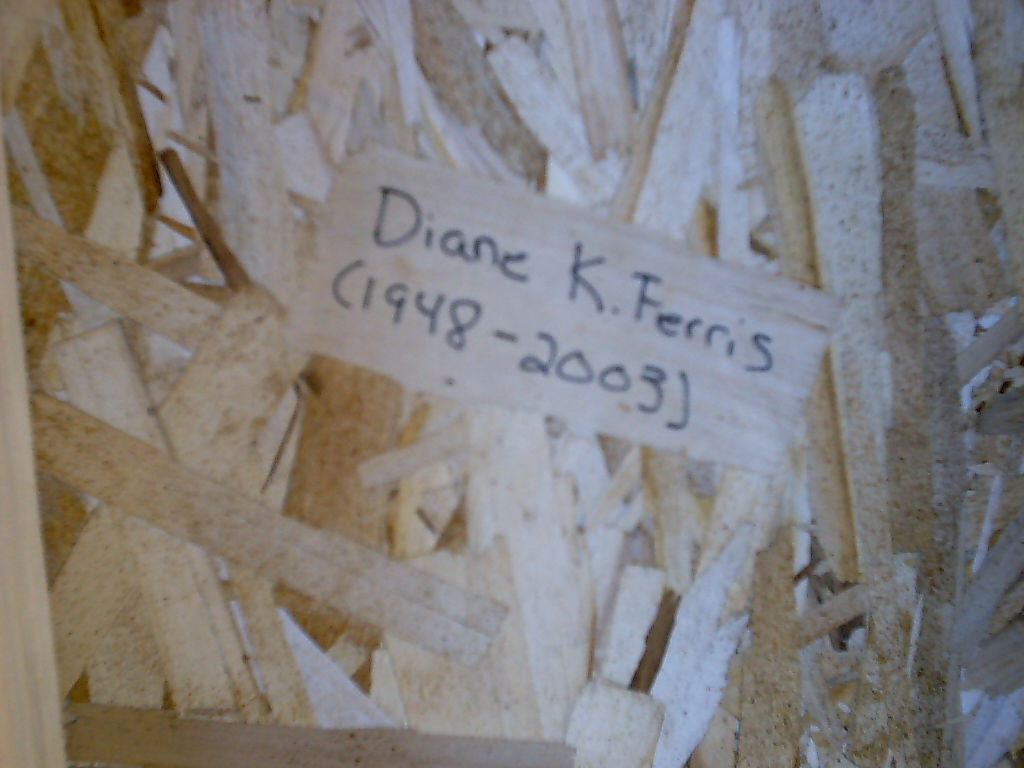

One of her last business efforts was to buy me a house. She put an offer on a house the day before she died, for me and for my father to live in when he came to visit me. She wanted to make sure I had a steady, safe place to live as a person who is deafblind with kidney disease. Since she died the next day, I did not get that house. But my father honored her wishes and he bought the house I currently live in. Make no mistake, my father never would have bought a house and let me live in it for just the cost of expenses if it hadn’t have been her plan all along. A few years ago, he turned over the ownership of this house to me.

I have often complained about this house and its upkeep. But truly, I always have known that this is the house that Diane built. It was her years of hard work and good money management that even made it possible for it to be bought, mortgage-free. It was her desire to leave something behind for me so that I might have stability that allowed it to happen. This house has allowed me to have and raise my children in comfort. To start a business, to even have a steady place for my husband to land so that immigration was happy. To live through short-term unemployment, long-term disability, and an unpredictable future. I know that I am privileged to have this house. And quite often, I look around at the safety of the walls, still strong even when my kids colored on them, and have a physical representation of her love for me and in turn the grandchildren she never got to meet. This house has been the foundation of my family, and without it, I would not have been able to offer them the stability and safety that my mother gave to us.

My mother wasn’t perfect, of course. I have written here and elsewhere about some of the issues I had growing up as a blind person and how hard it sometimes was to live with an uncompromisingly tough mother. But I write to help other parents of disabled children avoid some of those pitfalls. I have long since gotten over any anger that I had from those experiences. I even value them in many ways, because now that I have a child who is trans and on the autism spectrum, I use my mother’s mistakes as my own strengths. I don’t know that I have always known what to do with my daughter, she challenges me at times. It’s is probably not unlike the experiences my mother had raising a daughter who was losing her vision and hearing–and she didn’t even have the internet. But because of my own experiences with my mother, I resolved early on that no matter what—my home would be a safe place for my children. It’s a place where they can be themselves and feel safe to explore who they are. I still talk about the values my mom taught me, like hard work, education, and how to fit in to society’s expectations of you. How you should dress and act. But I also try to see more of the uniqueness they have to give and try to help them figure out the best ways to express it. I could have only known to be conscious of this by experiencing some of the harder aspects of the relationship with my mother.

As we now know, family trauma can be trans generational. I know some of my mother’s trauma was passed down to my generation. And maybe even to my kids (probably in addition to disability trauma). With my mother’s upbringing (and make no mistake, her mother had her own generational trauma) she could have been an absolute horror as a parent. But everything she did and who she was, was about giving us a better life than she had. To moving us forward as a family and improving the opportunities for us. In a single generation, she managed to erase poverty, abuse and violence, alcoholism, and chaos from our family. She was a tough, hard working women with high standards and very little tolerance for drama. But she also tried to be very fair and kind. I have lots of flashes of memories of her being so happy to see me and of her being so excited about a new opportunity I was about to take on. It wasn’t all hard-as-nails, there were many fun and compassionate moments, too. But my mom was a tough mother, you can’t get around that. And I think that was her way of shaking off her past and giving us the opportunity to live a better life than she did growing up.

My job is to take it to the next step. This is also why I have tried to look honestly at some of her mistakes and see where I can make improvements. How can I take the best of the gifts I was given from her and take them to the next step and make them better. My kids know all the links in the chain I brought forth from my mother. I expect them to show up, be presentable, work hard and value education. I can hear her speak to my kids in my head sometimes. Sometimes I channel her for them and tell them what she is saying. Sometimes I soften it. Sometimes I try harder to look at them for who they are and acknowledge how hard they are trying even if it’s not quite up to snuff. Sometimes I try to find more creative solutions for our conflicts than she might have. But this is just my way of continuing the links in the chain. I don’t know if I’m managing to do this raising a family thing, balancing work and home thing, and being a woman thing any better than she did. The times are different, my situation as a disabled person is so much different. It sometimes feels like apples and oranges and very hard to compare. But I know that she would expect me to carry forward what she did and improve on it. She would have higher expectations for me, and so that is what I have tried to live up to.

I asked her once, just a few days before she died, what she wanted me to tell my future children about her. She said that was up to me. I don’t know if I’ve done enough to tell them about her. They only have a vague notion that I had a mother whose name was Diane, and they have this idea that she was tough. But I don’t think they realize how much of her is in them. And how much of her has been a part of their growing up. She is ever present in this house that she built for my family. They know her values, they live them. And they know that in some of the ways we have been privileged as a family, it is directly because of her and what legacy she has left us.

Everything that she did is still here. Every accomplishment she earned, we still benefit from. The chain cannot be broken.