See Also:

What’s the Matter with Guide Dogs Chapter 1: What Happened at the Airport?

What’s the Matter with Guide Dogs? Chapter 2: Marra and Jats-The Gold Standard

What’s the Matter with Guide Dogs? Chapter 3: The Strange Story of Barley

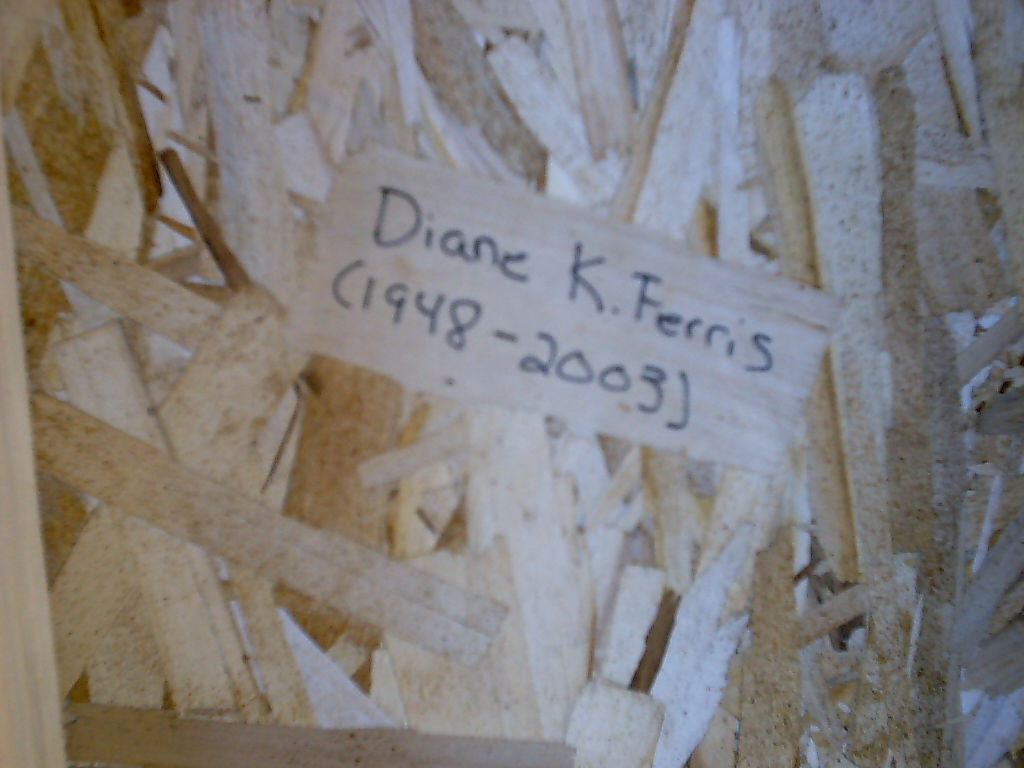

After my experience with Barley at Guide Dogs for the Blind in Boring, Oregon, I thought the issue was that particular school just wasn’t putting out high quality dogs. They were putting out too many, too young, too raw and too fast. So, schools are different. Huh. Okay, then let’s go back to where it all began at Guide Dog Foundation for the Blind. It didn’t happen right away, though. I had pushed to get Barley in the window that was 5 months before I gave birth, Nik moved down from Toronto, we started our immigration journey, and he got a job. When Barley was retired early, I lost my window. Although Nik was able to get Sully in 2011, I would not go back to get Marra until 2014. Our experiences the second time at GDF were a bit of a mixed bag. I got a really great dog with the best trainer I had ever had. Nik got Sully, and Sully is a complicated issue.

But first, a disclaimer about training staff:

I’ve already mentioned some trainers in this series by first name, and now I am going to go deeper and mention a few more. I want to be clear that I do not think these trainers are bad people. They are not the villains in my story. They are mostly hard-working folks that put in long hours and don’t get paid especially well. You don’t major in guide dog training in college. There is no real accreditation that sets universal standards. Most trainers are animal lovers that work their way up from jobs like kennel worker and put in years of apprenticeships. They generally try their best and want to help. Doug, Sioux, Mike, Dan, Kat, and Other Dan have been generally nice to me and seem sincere in wanting to do good work. I do not have issues with them, personally. I mention them only as a means to illustrate my first-hand experiences. What I am trying to bring to light through my story is more of the overall trends of lowering quality in the guide dogs that are being produced today and how there is no real quality assurance at all that is consistent. And that this issue affects us blind handlers the most, although we have the least amount of power to say anything about how it affects our real lives.

Sweet, Sincere, and oh So Very Soft Sully:

I met Sully in my house late at night after Nik took the train home from the airport. Sully was a sweet, squirmy ball of excitement, but Nik was exhausted. His trip home from the airport was more akin to the one I talked about in Chapter 1 of this series, though not quite as bad as no excrement, barking, or blood made any appearance. Still, it was a tough go for them.

Nik had asked for Doug to train a dog for him, but Doug was doing more field work now and so a compromise was reached. Nik went to the training center for two weeks and had Dan as a trainer. Doug was going to come to our city in a couple of days and finish off the training with the two of them for an additional week. This was a time period when all the schools were trying different models to reduce the 26-day training period to just a couple of weeks. Nik spent two weeks with Sully and Dan at the center, then Doug was to spend one week with us working with them at home.

Dan was a young, nice guy, very affable and good natured. Very proud to work as a guide dog trainer. Smelled horribly of cigarette smoke to the point where you always knew he was coming from 50 feet away. Dan’s dogs had a reputation of being very well behaved and had a high level of decorum indoors. Sully had impeccable manners. He always sat still, he never begged for food, barked, was incontinent, or chewed up anything. I noticed right off that he was of different stuff than the squirrelly, puppy-like GDB dogs. He would eventually become our business’s honorary receptionist and everyone loved visiting Sully.

Sully, however, was not a very good guide dog. I started noticing things early on. He didn’t get the gist of the job. He was trained with food rewards and was rarely, if ever corrected with a harsh leash correction. He always had this sort of expression of confusion the whole time. Once, we were in Vancouver, BC and he practically gave me a heart attack because he took Nik out on this road where cars had started coming around a corner (he had the right-of- way, but went at a steep angle that drew him into the other lane.) So, cars were coming around from a sort of blind corner, and Nik was trying to straighten Sully out, and Sully was so flustered that he pooped in the middle of the road. The cars were coming, they weren’t going to be able to see them until the last second, and Sully is in a squat with a confused look on his face. I pretty much stopped completely trusting Sully as a guide from that point on.

Nik took a lot longer to get that Sully couldn’t guide well. Nik has excellent O&M skills with excellent echolocation. Nik can pretty much walk around without a dog or a cane without too much difficulty if he is familiar with the area. Once, our Christmas Day got snowed in, so my twin’s father, the wheelchair user, was stuck in his house. So we packed up our whole Christmas–all the presents and the food and everything–and walked down to his apartment a few blocks away. Nik was carrying so much stuff, and he walked right down the middle of the snowy street perfectly with no cane and no dog. (There were no cars and it was easier to walk in the street than the sidewalk, as it had been cleared a lot more.) Nik is too skilled for his own good sometimes.

When you have some vision like I do, the guide dog trainers stress that you need to trust and follow the dog even if you can see something coming at you. But when you are totally blind, they just figure they don’t need to worry about you “leading the dog” too much. But Nik did not have a good fix on when Sully was guiding him and when he was guiding Sully. So, even though I could tell that Nik was doing more work than Sully was, I do think it was genuinely hard for Nik to tell.

So, what was Sully’s problem and why did he make it through training? There are many theories.

- Sully was puppy raised by a very famous actress. He was sponsored by a big corporation. He was named after a celebrity (Sully Sullenberger, the pilot who famously landed the plane in the Hudson River) and had some ties to related organizations. There was a feeling that Sully couldn’t fail. He was a beautiful golden retriever. People said he looked regal. He was also super empathic and sweet. But he never struck you as being particularly smart. He might have been a great PTSD dog or therapy dog, but maybe he did not have the brains to be a guide dog. Did the pressure to have him succeed get in the way of quality standards? We wondered if Sully was “passed through” when he should have failed because of his famous and high level sponsors.

- Was Dan just not a good guide dog trainer? He did well with Sully on the behavior side of things, but not the guiding. In the years after I got Barley, guide dog schools started doing massive staff layoffs. Supposedly it was a cost cutting strategy. Get the older, more experienced trainers out before they rack up the higher salaries and pensions and get new, young trainers in. Guide Dog schools laid off entire training staffs and hired untrained young folks. They were eager and meant well, but they didn’t have the same level of mentorship and apprenticeship that was common in the past. Sully just didn’t get the level of training he needed.

- Doug ruined him unintentionally. Doug came from old school leash correction philosophy. If you remember, Doug was the one who would put his hand over mine and show me how hard to yank on the leash. In the few days that Doug came out after Nik had brought Sully home, they worked on street crossings while pulling a stroller. In an attempt to teach Sully to use the curb cuts, Doug did a strong leash correction with Sully. I wasn’t there, but Nik said Sully just dropped to the ground on the road and wouldn’t move. He was crushed in a way we had never seen a dog react to correction before. Since then, Sully seemed to start pulling way out into oncoming traffic in a wide arc instead of crossing the street straight. He took the lesson, but got it wrong. instead of aiming for the often 45 degree angled curb cuts, he thought he was supposed to arc way out into traffic. And he lost a bit of his spirit after that. From then on, Nik–well all of us–completely changed the way we crossed streets to accommodate Sully. We would always cross the street so that Sully was on the outside of Nik and the intersection, so he could not go into traffic. This might have meant we crossed an intersection three ways instead of just one to keep Sully on the outside from the intersection. All of the ways we walked with Sully were a strategy to accommodate his behaviors. When I got Marra, I often walked in front so he would just have to follow her. We walked on certain sides of the street and went certain routes all to accommodate him. Nik was guiding the guide dog.

Sully was a very soft dog. He was the product of the newer philosophy to make dogs easier to handle and to need less leash corrections. Doug came out to work with us again, and I think he saw how sensitive Sully was and how leash corrections did more harm. When talking about the old dogs vs. the new, Doug had said something to the effect that he told them (the breeding staff) that they were going to have just as many problems with the soft dogs than with the former, hardier dogs. He also told Nik that Nik was doing more for Sully than Sully was doing for him and that Sully had pretty much “washed out” which is an expression that trainers use when a dog has just decided “fuck this shit! I am not guiding anymore.”

Sully did enjoy walking with Nik, just not guiding. And Nik loved Sully as we all did and was in denial. It came to a head one day when we had all gone to a Dairy Queen. Nik had to leave early to catch a bus for work and the kids and I were finishing eating. Ten or 15 minutes after Nik left, I started noticing a bunch of people looking out a window and exclaiming things like “what is he doing? Is he blind? Is that a guide dog?” I love it when non-disabled people spend more time gawking than just asking someone if they need help. I quickly gathered up the kids and went outside. Sully and Nik were wandering aimlessly in the parking lot, completely disoriented. Parking lots are hard for blind people, and it was way too big of a job for a dog like Sully. Nik was pissed because he missed his bus, Sully was just sad and confused beyond any kind of usefulness. I put my foot down. I said, “you have to retire this dog. He can’t guide and you cannot get mad at him for not doing something he has demonstrated for years that he cannot do. If you are going to take him places, you must not use him as a guide, you must always have your cane.”

Nik let Sully come with him when Sully wanted to, but shortly after that, Sully started refusing to work sometimes. We would go to my kids’ father’s apartment every night to help him out on alternating days. Nik would call Sully and Sully would pretend to be sleeping and not move, even though his eyes were moving around and his ears perked up. It was hilarious. But he mostly still liked to go to work with Nik during the day. He would go in harness, but he really had very little guide “duties” that he was held to. He retired like this around 7, after about 5 years of trying to work with him and getting trainers out to work with him. He spent the rest of his life just hanging with the fam and going on low-stress walks. He died last year at the age of 13. I still miss him. He was such a sweet dog. But sometimes I think he missed his true calling in life. He should have been a PTSD dog for a veteran or something.

I agree with Doug. What I have observed with the issue of “soft dogs” is that they do not seem as smart as the hardier dogs like Mara and Jats. I don’t pretend to be any type of expert on breeding, so I honestly don’t know if this is a breeding issue or a training issue. But this is what I observe:

- Soft dogs don’t seem to roll with mistakes as well as the tougher dogs. This is very important, and I think there is an aspect of this that trainers don’t have enough experience to understand. When you are blind, you WILL make mistakes with your dog, especially in the beginning when you don’t know them so well. It is sometimes hard to tell whether your dog is screwing around or when they are trying to tell you that there is an obstacle in the way. As a blind person, you at times WILL scold your dog when they are being entirely correct in their behavior, and you will praise your dog when they are screwing around. Hopefully it doesn’t happen too often, but it will happen, especially in the beginning. If a dog can’t roll with that and bounce right back to doing what they were doing before, they lose their training and their will to work. A blind person needs a dog who doesn’t take things too personally, will bounce back quickly after a bit of confusion, and who blows you off when you make mistakes. Basically, a confidence in themselves and what they are doing that goes beyond “perform a trick, get a reward/avoid punishment.” The older dogs had this, the newer ones are less likely to. I recently had a conversation with a guide dog trainer about this and she was defending the newer dogs and saying the old dogs were kind of bullies. Well, maybe, but you NEED a confident dog that knows when to say “screw you, I’m right and you’re wrong.” The new dogs are too sensitive and try too hard to please you to do this. Sully was crushed–CRUSHED–any time he didn’t do the thing Nik wanted him to do, even if Nik was wrong. He got confused. He had trouble bouncing back. He did not have the confidence to think on his own. He washed out early largely because of this.

- Related to this, newer dogs don’t really do intelligent disobedience like the older dogs did. This is when a dog will refuse a command because it is not safe. Doug used to tell us to tell the dogs to go forward at a street corner when traffic was rushing right in front of us, but they wouldn’t budge. Now, the dogs can’t do this. (I’ll talk more about this when I talk about Mia and Cobey.) They have lost that for the most part. This was a most important skill. Sully literally walked INTO traffic with cars coming at him because he thought this is what Nik wanted him to do. He feared displeasing Nik more than he feared being crushed by a car. He was so overtrained that he lost even basic self preservation. I would take a bully dog over that.

- The newer dogs lost the overall context of the job. They are so into pleasing their handlers that they look at each task as an individual trick rather than using strategy and context to understand the over all job. YES, dogs CAN generalize, understand context and strategize. I’ve seen it again and again. All dogs are different and this will be true to varying degrees, but it does seem like the newer dogs don’t do this as well. They get overly distracted by food rewards to the point where they lose the overall gist of their skills in different situations.

I’m not saying that we should go back to severe leash corrections, but I do think there is a compromise, and I think I found it in Marra.

Marra’s Training:

It’s sort of a no-no to pretend that any trainer is better than any other trainer and to ask for a particular trainer, so it has to be done a bit on the down low. A little nameless birdie may have told me when Mike would be up for class and that he was the best trainer. So I asked for him and was lucky enough to get him. I was a bit worried to go back to GDF after Sully. It was now 2014, and two years earlier, the entire GDB training staff–the largest in the country–had been laid off due to cost cutting measures. These folks scattered across the county among the guide dog schools, and several had landed at GDF, including the new training director. I saw from other people’s experiences with guide dogs that GDBs methods were getting spread out everywhere. The right hand leash issue, the squirrelly, young dog issue, the low expectations, the route trained dogs that were dependent on routine memorized routes rather than thinking. This was another issue with Sully. He was very, very routine dependent. He did ok for 5 years mostly because he memorized routes. But he also did not want to deviate from those routes. He would get very stressed to go off a route that he was familiar with and it was a problem. It looked like it didn’t matter where you went, that GDB low-end assembly line philosophy was spreading everywhere.

I had met Mike briefly in 1993, when other trainers would wander through the dorms occasionally. So the main thing I knew about him was that he had been there for at least 21 years and was not a GDB import. I had an extensive interview with Mike in about June of 2014. We probably talked for about an hour, and it was the most extensive interview I had ever had. Because of my past experiences with Mara, Barley and Sully, I felt like I really had a good grip on what I wanted and didn’t want. I wanted a dog who was well behaved in public like Sully and Mara. I wanted a dog that was not routine dependent like Sully and to an extent, Barley. I wanted a dog who could target things and could be taught to target things easily like Mara and Jats. It was a nice conversation that I thought was incredibly thorough and I felt like I had been heard.

In training, Dan and Nik had had some kind of good natured conflict about Nik going off to a deli on his day off. It was still like that in guide dog school, you couldn’t set foot outside the dorms on your own. Nik eventually went to the deli with Dan following behind, but Dan was probably supposed to have the day off that day or something. I can’t remember the whole deal. So when I got there, I was asked if I was going to go rogue like Nik had. (Had my “mad escape” from GDB– where I ran 50 feet as fast as only a pregnant blind person can–preceded me? Were we now the couple that couldn’t stay put?) I decided to be straight up about it. “You guys know guide dog school is like a benevolent prison, right?” I said. “I admit, I struggle with this. I am never going to trust you completely with myself. I will always have an ID, a credit card and the number of a cab company ready to head. I will always be searching for the escape route and planning my route back to where I can control things. I will always feel smothered, surveiled and like you all need to just get away from me. But in general, my plan is to be compliant and do the training.”

And that is how I got the “little freedoms” I got from Mike. Meaningless little things like that I could go out on my own at night around the several acre campus and practice with my dog on the practice blocks or walk in the now defunct garden that I was barred from 21 years prior. Or that I would be allowed to go explore a mall or walk to a coffee shop when my training partner was on his walks with Mike. It was a bit of freedom theater, but it helped.

Marra was a delight. She was happy to meet me and was engaging and had very little issues in the dorm room. She was relaxed and friendly. I did the same walk with her on leash to a dining room chair that I had done before with Mara. This time, it was still a bit nerve wracking, but I knew it would get better quickly. (The name was total coincidence, by the way. I about fell off my chair when I heard it. In fact, when they told me her name the first time, they said it like Mara. Mara was pronounced like Maura Tierney. Marra was pronounced like Sarah.) The next walk was on a park path with no curbs or obstacles. But Marra stopped at each path and looked up at me, showing me where it was and asking me if we wanted to turn there. I did choose to turn on a few and not turn onto others. “Oh, my goodness!” I exclaimed. “She is showing me the paths and asking if I want to go on any of them. This is almost as good as having a cane!”

“Well, you asked for that, right?” Mike said. Then he explained to me how after our interview, he trained Marra to my requests. I talked a lot with Mike about the training process itself and how he was trying to change with the times but keep the standards high. He talked about how he always had to be a bit more creative than some of the other trainers who were larger in stature and did a lot of strong leash corrections. As a smaller guy, he always had to get the dogs to respond to praise more than they did. When food rewards became a thing, he tried to use them where it made sense but not depend on them entirely. He knew that I did not want food rewards for Marra, so he trained her both with them in the early stages, but then without them after she learned a skill. He asked me to compromise, and use food rewards for a few days, to get her more focused on me than on him. I did that, and then by the end of the first week, we had completely left food rewards behind. When I got home, I used them at first to teach her a few new things, and every once in a while brought them out just for fun, but generally we used them very seldomly. Marra came ready to go with many target words already known. She could target elevators, trash cans, chairs, doors, etc. We even worked with the trainers at their sister program, called America’s Vet Dogs, to do some signaling for when there was a knock at the door.

There were about ten people in the class, but there were 5 trainers. Each trainer had two students and mostly did their own thing with the two students, although some days we would all go to the same place together. I was with a student from Brazil who did not travel independently at all. He could not do street crossings independently. He was a professional in law, I was told, and he had drivers and assistants to do everything for him. I asked Mike how he could qualify for a dog. Mike shrugged. He said they try to select people who will benefit from having the dogs, but sometimes the benefits may be more social than navigational. For my Brazilian partner, it was likely more of a social bridge to acceptance for him. Hmmm, okay. I know that there are serious cultural barriers in some other countries for blind people and maybe that is worth it. But it also seemed like a waste of a trained dog. A person like that might do better with a dog with good obedience skills and decorum, but no guiding skills. (a dog like Sully?) It made me wonder if they trained dogs at different levels specifically for how people will use them. At what point is a dog still a guide dog?

The way they seemed to train dogs at that time was kind of interesting. They seemed to adopt some of the short kennel time of GDB, but still keep training standards high (at least for Marra. I did not see a lot of the other dogs this trip because of the 1:2 ratio thing.) Although I am sure the dogs are well cared for, being in a kennel for months on end is not good for the dogs. It stresses them out. It can be boring, it separates them from people and home life. It IS a prison. Mike indicated that GDF was trying to give the dogs as few transitions as possible and keep them in the kennels as little as possible. Marra went from her dog mother to her puppy raisers, to Mike and the kennels and to me. Her kennel time was low, only about 12-14 weeks. Mike had her the whole time, with his string of about 4 dogs, he was then in 2 classes for the month training with his 4 dogs to their blind handlers, and then he started the process over again. And a very well trained dog came out of that 12-14 weeks, with one trainer doing 4 dogs at a time. Maybe best of all, you trained with the trainer who had been with your dog for the last 12 weeks and knew exactly what they knew. And they could overlap and ease the dog into the new relationship.

The Facilities

This was the same campus I went to in 1993, but the entire dorm building had been remodeled. We all had single rooms now. It was a bit less like a house and more institutional, but overall it was fine. Basic, but fine. We still utilized the practice blocks they had on campus, and took the bus or vans to other locations. We worked in Smithtown, and Huntington mostly, but also went to Queens to do subways and the like. They still had no other “waiting” places, so we stayed in the vans a lot when it wasn’t our turn. With one trainer and two students with close by places to train, we took about 4 walks a day with the dogs. The waiting time was usually never longer than 20 or so minutes.

Level of Custodialism:

It was a little better than in had been in 1993. No longer were we barred from rooms of other classmates and no more separation of genders by wing. I, of course, had a bit more freedom than my classmates, basically because I asked for it and they let me. But you were still stuck there and there was a night babysitter of course, but she pretty much let you be. My training partner highly valued access to alcohol, so it was procured for him but weirdly, they made him drink outside of his room. So sometimes I would see him in the little snack lounge drinking beer and listening to Portuguese music.

Although Mike didn’t really do this, there was still a habit for staff to say that anything you did independently was because you had vision. I highly doubt I had the best vision of the group. In fact, I know I did not. But it was constantly said that I got to do some of the things I got to do, (like work my dog at night on campus without supervision) because I could see. This was funny to me because I am really night blind, and I actually asked to work at night because I knew I would have more of a challenge working at night than during the day. In any case, there were people who could see better than me who did not get these “little freedoms.” But it is probably because they didn’t ask.

I did have to try to back Mike off on standing right there and telling me every little thing. I don’t mind this on the first day or two when you are just getting used to the dog, but by the third day, you really need to work on trusting the dog and trying to see what it feels like when they are telling you things. So, for example, Mike would say “There is a set of four stairs coming up in about 15 feet.” Well, thanks for telling me, now it doesn’t matter what my dog does because I already know what is coming. When I asked him to back off, he did a bit, but seemed surprised I didn’t want all of this visual information. But Mike! I won’t have you with me when I go home! How will I know how it feels when this dog is telling me we’ve hit stairs if I anticipate them now? Again, this comes back to the traditional vs. structured discovery style of O&M. Guide dog trainers are largely not trained in O&M, at most they’ve been to a few CEU classes–likely taught by sighted traditional O&M instructors. They do spent some amount of time with each dog under blindfold, but are never left alone without another sighted trainer with them telling them everything that is ahead of them. They don’t really have a good idea how a lot of us travel.

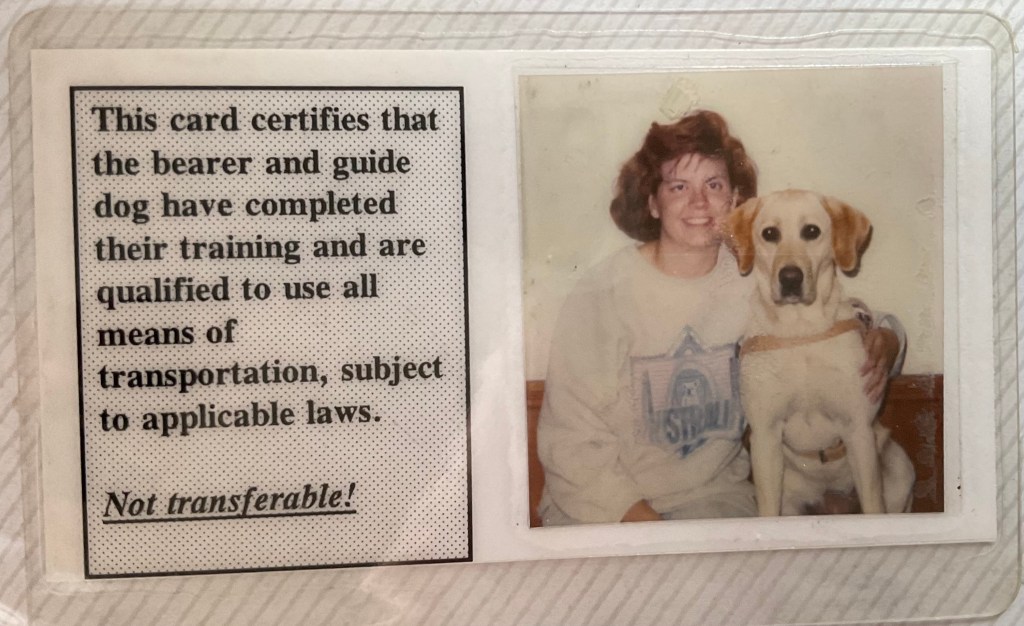

One thing that was a definite improvement was that upon graduation, I was able to take ownership of my dog. This has been a hard fought for right of blind guide dog owners. I first was able to own my dog when Mara was about 8 years old. They had changed their policies and sent me an email that gave me the option to sign ownership papers. I was at work and I cried. I sent back the email indicating I wanted to sign the papers and got down on the floor with Mara and hugged her. She was really finally mine! Some schools act like it shouldn’t matter, but I’m sorry. It does. Again,why do they vet us so heavily but yet not trust us to own the dogs after we graduate? Do they not trust their own program? With Marra, I was given ownership papers upon graduation, which is how it should be.

There was one thing that really bugged me, though. One of my classmates was a staff member there. She worked in client support services (which is where every single blind staff member who works at guide dog schools is placed.) I thought she was treated horribly. On the one hand, I get that this is her own time and they wanted her to have time to concentrate on her own dog training and be off the clock–which is totally fair. But you would get into a discussion about guide dogs with her and from across the room, a staff member would cut her off and say in a condescending tone “Now, Jane (not her real name), you know you are not allowed to discuss guide dogs with the clients.” She who was on her third or fourth dog couldn’t even tell a story about a past guide dog. And you would ask her a simple question having to do about say, purchasing a new leash (like would I come to you or have to contact the training staff) and they would rush in and be all, “are you asking Jane questions??? She can’t answer any questions!” But the worst thing was that she said she wanted to be promoted but she had a–shall we say–a sighted glass ceiling she could not break through. The next promotion up required that the staff member stay over night with the students occasionally. And they would not let a blind person do that, and she could not get past that requirement. I understand the babysitter thing to an extent. I get why you don’t just let 10 random people have the run of your entire campus alone overnight. But really? a blind person couldn’t babysit us? To GDB’s credit, they had blind people in these roles. It really hit home that these people really do think of us as second class citizens.

Graduation:

Again, graduation at GDF was a reception with only puppy raisers, sponsors and handlers invited. They did have a filmstrip of us that they had taken throughout the training there, and they showed it to us twice. Once before the guest arrived so that they could describe it to us, and then once when the guest arrived we sat through it in silence. I thought it would have been better to describe it to us with the guest there, because it would be good modeling of accessibility and it might have been more interesting for everyone to have some back story. My puppy raisers were a lovely family with children, and they did get to visit with Marra this time. I think it is important to see how much your dog is happy to see the puppy raisers. It shows her past, and that she had a life before you, and that there is some hurt and loss involved during these transitions. That is important to keep in mind and that gets put in your face when you see how excited the dog is to see the raisers and how sad she is when they leave. The family was very respectful about it and I enjoyed meeting them. Overall, the graduation was casual and not very much inspiration porn at all.

Bringing Marra Home:

The main transitional problem Marra had for a couple of weeks when I first brought her home was that she chewed through about 4 leather leashes. And to be fair, I should have mentioned this in my first chapter on our airport trip. She did chew through her leash in the airplane on her way home. So it wasn’t completely uneventful. But think of it this way, I guided her from the airport to the hotel without a leash. She chewed it in half down too short to be useful. I only had the harness to hold on to, so I could not drop the harness handle, do any leash corrections, give her a little nudge, anything. And we still did ok making it to Nik’s hotel, including meeting Sully! This was a good guide dog! She chewed her leash and a couple of shoes in the first few weeks, but that was it. We really had no other problems.

But she was an energetic, young dog. She would get too excited and pull too hard sometimes. I specifically remember having her down in Pioneer Square in Portland during a Christmas event. So this was in the first couple of months that I had her. There was a lot of excitement and she was sniffing around with her head down and getting on my nerves and so I finally gave her a fairly hard leash correction. And she dropped like a sack of potatoes. Oh! MY! These dogs are soft! I felt bad and I vowed to never do that hard of a correction again, (and I don’t think I really have.) But here is the kicker. Unlike Sully, who would have been useless and sulked for hours, after I squatted down and gave her a few pets, Marra bounced right back to it and was fine. All was forgiven and we moved on in life. I realized both that I did not really have to do very serious leash corrections with her (a small little tug to pay attention was all that was needed when she got distracted.) I also realized that this dog has some wherewithal to get on with it and bounce back. She has confidence.

Mike told me that what we are asking guide dogs to do is easy. The hardest part is to keep them interested and motivated to do it. He had high expectations for the dog and at least understood that blind people are all different and come with a variety of skill sets.

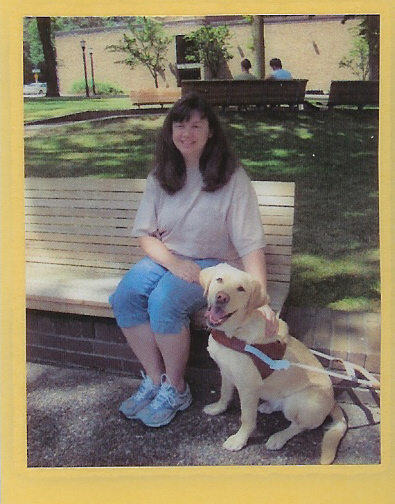

Marra was still not as savvy as Mara. We’ve gotten into a few jams that she just couldn’t figure her way out of in the way that Mara would have. But overall, she has been an excellent guide who came very well trained both as a guide and with good decorum. She came to me healthy mentally and physically and was very “finished off” as far as being ready to hit the ground running as a guide and work right into my life with very little work that I had to do at home. She eventually developed hip issues and leg tremors, but I had many good years with her before she retired.

Marra’s timeline:

Born: April 3, 2013

Puppy raisers: June 2013 to June 2014 (13 months)

In for training: July 2014 to mid October 2014 (14 weeks in kennels)

In class: October 15, 2014 to October 31, 2014 (16 days,age 1 year, 7 months)

Working Guide: November 2014 to October 2023 (9 years)

Retired: October 2023, still living with us as of this writing.

Died: November 30, 2023 (10 years, 8 months). Marra suddenly and unexpectedly died just days after this post was written. She died of hemangiosarcoma, a spleen tumor that is hard to diagnose.

Final Impressions:

It’s probably not entirely fair to compare Dan vs. Mike in the context of Sully vs. Marra and how successful they were. The data pool is way too small. And again, I liked Dan, he was a nice person who did seem to take a lot of pride in his job. But he was in my class, too, in 2014 and I watched him with the other students. He was not as experienced as Mike and did not at that time have a real knowledge of how blind people traveled or worked dogs. In every profession, there are younger, less experienced people who need time to learn and grow with the job and should be fostered to do so. What I noticed at this round of GDF, though, was that Mike was holding up an old standard and it was not being held up throughout the rest of the staff. In this way, how can one blame the Dans when they aren’t being given a lot of guidance in how things could be done better? When I was there, another older trainer named Barbara was there. She was soon to retire and she came to visit me a couple of times. She wanted me to meet with John. Remember John from 1993 who called Nik “fat boy?” I was not a fan of John’s back then. But Barbara was very excited and insistent for me to meet with John as he had retired due to Alzheimer’s. He was still on staff as “Head Trainer Emeritus” but I don’t think he had any duties. I agreed to meet John and I brought a picture of our class (as seen in the last chapter of this series.) I don’t know if he remembered me but he seemed to remember Nik. I only visited with him and Barbara for a few minutes, but there was a very wistful, “it ain’t like it used to be” vibe. I hugged him and he said, “back then, we trained good guide dogs. You were trained well, too. You know how to do it and you need to keep it up.” The idea that he seemed to be trying to get across was that he taught us the right way, so no matter what was going on now with the newer guide dogs, I had been trained well and knew how to keep that information alive and pass it on, as well as make sure my own dogs still lived up to it. I felt like I had won the jackpot with Marra as one of the last old school guide dog with one of the last old school trainers. We are still very fond of Doug, who is a very nice man who has been very helpful to us over the years. But Mike is hands-down the best guide dog trainer I have ever worked with.

In our house now we have three dogs. I will talk about our new dogs, Mia and Cobey in the next chapter. But Marra remains the Head Guide Dog Emeritus.