I have been working on cleaning up and fixing my computer that I hadn’t used in over a year and found this essay I wrote maybe 2-3 years ago for a Beacon Press publication on the disability experience in religious organizations. I was told that the editors/authors got so many contributions, they changed their strategy to just include side bar pull quotes from the contributor’s essays. After reading it, I thought, “yeah, that is pretty spot on about what happened back then. What the hell. I’LL publish it.” I will say that my last interactions with the church were probably around 2017 or so. I do not know much about what the UUA or any individual churches have possibly done to be more inclusive of diverse members since then.

The first time I ever went to a Unitarian Universalist Church, the door was locked.

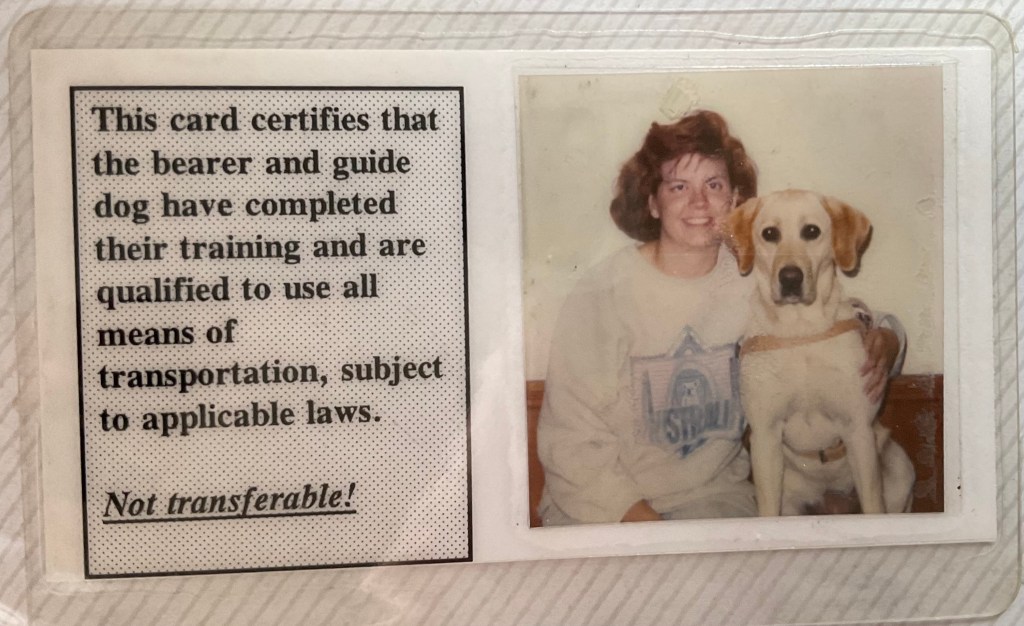

I am blind and hearing impaired and at that time was pregnant with twins, and my parenting partner, Dwight, has quadriplegia and uses a wheelchair. We were excited to get up on Sunday morning and have this new experience. Both of us were new to the neighborhood, and really wanted to find a positive and supportive community with which to raise our children. I had researched Unitarian Universalism online and it looked exactly like what we wanted. A church community low on dogma, open to diverse families, and high on doing good deeds to make the world a better place. We had noticed a long, triple level ramp that had been built on the backside of the building as we had walked by in previous weeks and took it as a good sign that disabled people were welcome there. But when we arrived and climbed the long ramp on that first Sunday, the door wouldn’t open. We knocked but got no response. After waiting a few minutes, I told Dwight to wait there and I grabbed the underside of my protruding pregnant belly, as I had come to find was the only slightly comfortable way to walk anymore. I went back down the three levels of decline, worked my way around the church, and up the flight of stairs at the front of the building. I was welcomed when I entered the door, but not knowing the building myself, I had to ask several people to help me get to the back door where my partner waited so I could let him in.

In the ten years that I participated in Unitarian Universalist church congregations and activities, my family and I faced a lot of locked doors—both real and metaphorical. We worked hard to open them. Sometimes we had success, sometimes we did not. Sometimes it even seemed as if our work only caused the doors to get additional, sturdier locks. After years of this exhausting work, slowly my family gave up. I was the last hold out, but finally I didn’t know why I was there anymore, either. This is my story of being a UU failure. And how the UU church failed me.

My disability is a bit hard for people to understand. I have some vision and some hearing. Sometimes, it might have seemed like I had no problems at all hearing or seeing what was going on, other times I was unable to use my vision and hearing effectively without alternatives and accommodations. I have always understood that no one, not even my closest friends and family, can truly understand when I can or can’t see or hear something. They would regularly misinterpret when I needed accommodation or what kind. This has always been understandable to me, and I have never expected perfection. I never expect everyone I meet to be experts in ADA accessibility or in how blind, deaf or otherwise disabled people do everything. What I and most other disabled people like me hope for is to be included. We want to be welcomed and seen as contributing members just like anybody else. If something isn’t working, if we can’t access something, we want people around us to be willing to work it out with us until it works. To be adaptable to change and to prioritize inclusion.

This is why we were not too phased when the accessible entrance door was locked. Maybe someone just forgot today or didn’t grab it yet. No problem. It barely raised concern for us, and we enjoyed the service and afterwards, a few people came up to us and politely welcomed us. So far so good. But then it was locked the next week, too. And a few after that. It was locked approximately half the time we went. When we finally brought it up to the minister, we just thought it was a procedural problem. We knew there were a rotating number of volunteers that probably got the church ready on Sunday morning. I thought it just needed to be added to a checklist and the problem would be solved. I was shocked at the response we got.

The interim minister was very defensive. He told us that the door was not being kept locked to keep us out on purpose, but that the door got stuck a lot. This didn’t quite make sense to me because I was often the one who went around and physically unlocked the latched door, but I do suppose it was possible. We told the minister that we did not think the door was being locked or stuck shut on purpose to keep us out, but that the effect was the same. We couldn’t get into the building. I had newborn twins at this time, and between the wheelchair, the twins in car seats and their stroller, and my poor vision, it was quite a difficult task to get in the church. And it also meant that Dwight, or anyone else who needed ramp access, could not get in on their own. We asked that a solution be found, not that blame be sought. The problem got marginally better over the next few years, but never completely got solved. Even when we did get in that entrance, there was no on there to greet us, or give us an order of service like at the other entrance. In an old church, we understood the difficulties of architectural accessibility. Again, we did not expect perfection. But it would have been nice to feel welcomed on Sunday mornings instead of worrying what rigamarole we might be faced with to even get in.

If it was only the door, I think we could have managed it. But many other things became as much of a barrier as the locked door. It was a little bit like death by 1000 paper cuts–isolated incidences don’t individually seem that dramatic, but taken collectively, they wore us down. I have a severe/profound hearing loss and use hearing aids. I tried to mitigate my problems hearing the sermons by sitting up front. But it seemed to cause problems with the flow in the aisles when Dwight’s wheelchair blocked the aisle. There were spaces for wheelchairs in back, but then I would really just be sitting there, cut off from both the visual and audio aspects of the service. I found that the sermon transcripts were available to read after the service. This made me have an idea. Could I possibly get the sermon sent to me beforehand in an email? Then I could read along with it by having my laptop speech reader read it to me. A very kind woman asked the minister if he could do this. He declined, saying there was no way he could remember in time and have it ready even 5 minutes before the service. This was a different minister than the one who we discussed the stuck door with. These kinds of responses almost physically hurt, like punches to the stomach. They made me feel like I was asking for too much, like I didn’t matter, and like I wasn’t really wanted there.

The reason I stayed so long and kept trying were because of two things: One, this response to disability is not rare, it is universal in many places, so why would it be any different in this community? And the most important reason, because Dwight and I had champions there. There were a few people who always stood up for us and always tried to make things work with us. These were both individual congregants and sometimes staff. Our biggest champion in our early UU days was the Religious Education Director, Sara Cloe. If not for Sara, we would not have lasted more than maybe a few months. But Sara helped advocate for an assistive listening device for me and other hard of hearing folks, she advocated for the parish house to have a ramp, she sometimes advocated for rides for us when off grounds activities were occurring that we couldn’t get to on our own. She even advocated for a covenant group to be made to help specifically include us.

One of our problems was that when activities, such as covenant groups happen at people’s houses, we couldn’t go because the house would not be wheelchair accessible or on a bus line. Sara made it so a covenant group happened at the church, she even arranged childcare. She called it the “Family Covenant Group” and we did make friends with those families that I still care about and keep in touch with to this day. It was one of the lasting gifts that came out of our UU experience.

Another example about how things aren’t always perfect but can be made to work if people work together is our experience with the UU Family Camp. There was no way Dwight could go to family camp due to the inaccessibility of the sleeping arrangements and bathrooms, but my young twins and I went. Sometimes, when a disabled person has never experienced something, it is impossible to know what you might need as far as accommodations. I had never attended anything like a church camp before. This was also the first year that this camp was put on by the church, so kinks were inevitable. On the first morning, I went down with my kids to eat breakfast in the dining hall and then went back to the room I was staying in for just a few minutes to drop off some things and let my newly potty-trained toddlers hit the rest room. When I came out, everyone was gone. I didn’t know where they were so started walking around. Then my kids started happily playing in the sand volleyball court. So, we just stayed there and played. I didn’t really know what I was supposed to do. When lunch time came around, the people were back in the dining hall, so we returned there, and I got so busy just trying to figure out what the food was and help my kids through the buffet line that no one really talked to me and I didn’t get a chance to ask questions. Then, in the afternoon, everyone was gone again. Poof! So, we played on a nearby playground and just entertained ourselves. I was getting really distraught, though. It was just exhausting to try to figure out this campground and keep track of my toddlers and just figure out my own way around. And no one seemed to notice or care that we were struggling through the buffet line and all by ourselves all day. I ended up calling Dwight and asking him to come pick us up 2 days early. I made some excuse and left.

I felt like I failed but I didn’t exactly know how or why or what to do to prevent it. It wasn’t until a year later that I found out that there was a print agenda of activities with a map of where they would be that I was never given nor told about. They were all off doing different camp and religious activities and I was left behind. I did not know there was going to be formal activities that people would all go to together. Sometimes you don’t know what to ask! Again, it was Sara Cloe that came to my rescue and gave me the courage to try again. I told her what would be helpful to me. Could someone tell me what food is in the buffet line and perhaps help my kids and I get through it? Could someone just let me know what is on the itinerary and walk me to the activities? Sara and her two teenaged daughters completely came through for me that next year and the following year as well. The girls were always there the instant I came into the dining hall to grab a plate for one of my kids and tell me what food was being served. I always knew what activities were going on and where they were. I was able to participate in many activities and we all had a very good time. I was also able to help clean up when I was given the chance to be shown where to put things.

It was important to me that I was able to contribute to the community as well. A teacher by trade and training, I very much enjoyed teaching different religious education classes and working on the religious education committee. Sara was always willing to work with me. Sometimes, we would still be excluded, though. In each church service, we were told that if we wanted to be members, we should talk to a board member to take the next steps. Over the years, I asked to become a member on at least four occasions, but no board member ever followed through with me to tell me what it was that I needed to do. Sometimes, several people would go to an indoor playground after the service together so their kids could play, but we could not get there without a car. I understand that not everyone has a place in their car for 4 or 5 extra people, but when I suggested a different indoor playground that I could easily get to by light rail, I was told they didn’t like that one and they were sorry we just couldn’t go. I didn’t care so much, but it was hard on my children who heard through the kids about the plans and knew they weren’t going to be invited.

When my kids were about 5, several things changed in my life. Dwight and I were and still are friends and parenting partners. We never had a romantic or marriage type relationship. We were a family unit, albeit untraditional. I came to marry my now husband, Nik, and we had a child together. Around this same time, Dwight had become less interested in the UU church. He went largely because of me, and although he did try to stay engaged for several years, he tired of the exclusion. Because of that and due to additional health issues, he no longer wanted to put forth the energy to go. I kept going, but I imagine it looked as though I swiped out Dwight for Nik. Nik is totally blind andhas some facial deformity. When Nik started going to church with me, the tone seemed to change for many people. It felt like we were even more excluded. At first, I thought it might be that it looked like I divorced Dwight and quickly married Nik and it was just odd for people who maybe had some loyalty to Dwight, who was no longer around. But he was around in MY life, and so I tried to explain that to people in the nicest way possible. I did not toss him out for another man! We are all still co-parenting together! Its good, no worries!

But then another church member had a very public and contentious divorce. And I saw how people supported both her and her ex-husband. It did not seem like people were too judgmental about divorce here. So, what was wrong? People barely said “hi” to us. They didn’t engage us hardly at all anymore. It wasn’t everyone, but the climate had changed. I had also noticed it with the kids’ school as well. Nik is as outgoing and as friendly as they come, so what gives? I slowly came to the conclusion that it was because of how we now looked. Before, Dwight just was a basically good-looking guy sitting in a chair. With Dwight, my disabilities were somewhat more hidden because since he could see, he helped me out a lot. With Nik, he was Capital D-Disabled! There was no denying it. He looked different, he moved differently, and he was no help to me visually, so all of my low vision quirks were in full view. I had caught the disability cooties from Nik, and we made people much more uncomfortable than we seemed to when I was “coupled” with Dwight. One time, a person whom I had been acquainted with for years came up to me and started telling me about another blind mom who used to come to church with her husband who used a wheelchair. It took me a second to realize that he was talking about me and didn’t realize I was the same person. This slammed home for me that the change really had nothing to do with any “divorce” people may have assumed I had. Some people just really never saw past the disability at all.

This was when we changed churches, just to try something new. We went to a much larger UU church in the downtown of our metro area. Some things were instantly better here. They had assistive listening devices that mostly actually worked. At the old UU church, they were either broken, low on battery power or those speaking refused to use the microphones. The new church had braille orders of service and large print and braille songbooks. Instantly, we felt like we were considered and that we were welcome. There were a few people who were genuinely kind to us, one was again the religious education director. But the luster soon faded to a grey confusion.

On one of our first visits, a congregant came up to us and wanted us to join his group for disabled UUs. We were delighted. He was also vision and hearing impaired and was struggling to fit in. We also met another man who used a wheelchair. This man had also formerly gone to a smaller church. He said he quit going when he had gone to an evening event and had to knock on several windows before anyone would open the accessible door and let him in. (“Ah! That is familiar,” I shared.) He told a story about how he was out in the cold and rain and was literally having temperature issues and getting ill waiting and pounding on the basement windows while his wheelchair got stuck in the mud. That was his final straw at that church. We met and exchanged all kinds of ideas about how to make the church more welcoming to parishioners with disabilities. All of us had stories like these, and all of us sensed this defensiveness that occurred when we talked to the powers that be in the church about these issues. Most importantly, all of us had tried to find community and make friends but had mostly had the experience of just not getting past a very basic polite “hello” with most people. People were rarely openly mean, but barely said more than “hi” to us.

We decided that our approach should be to be more proactive. Instead of waiting for things to become problems and then be constantly put in the position of complaining, the UU Disability Committee (which we had invented on our own) would serve the church by helping it to become more accessible. We could do an accessibility audit and suggest changes to be made, and when disabled people had accessibility issues, they could come to us and we would help them work it out. We would also offer educational programs and events for the church and invite them into our world with fun events. We were excited to take this on. All we needed next was to make it official with the endorsement and support of the minister and board.

We couldn’t even get a meeting. Months went by and the minister was always too busy to meet with us and finally told us it wasn’t a priority at this time. Even though essentially we would be doing all the work, they didn’t want us to proceed.They felt it was too much of an undertaking. They were not even willing to put a blurb in the newsletter saying that we were a committee who could help with accessibility concerns. There was only so much we could do on our own.

And then one day I was in my son’s RE classroom and Nik had attended the service. When we met afterwards, he was upset. He said that he really enjoyed the sermon. The minister had talked about growing up black in America and the oppression he faced. Nik identified with a lot of it because of his own experiences as a blind person. As disabled people, we are a minority group that faces rampant oppression and civil rights violations. Although not identical, we face some of the same types of things as racial and cultural minorities, LGBTQ+ populations, and others. Nik greeted the minister on the way out and complimented the sermon. He said he found some common ground with it and identified with it. The minister, Nik reported, acted disgusted by what he said. He said, “I don’t possibly see how being blind is anything like being black,” as he walked off. He refused to shake Nik’s hand.

I know that one has to be very careful not to give the impression that because you may share some experiences of oppression, that does not mean you know what it was like to be black if you are not black. Or that you know what it is like to be disabled if you are not. It is also very important that we do not play Oppression Olympics, comparing who has the worst form of oppression as if it is a contest. But minority groups do share some common experiences that could strengthen and unite us if we could find those and work together. I did not hear the conversation, and I suppose it is possible that Nik’s wording was jarring. He is an immigrant and English is his second language. But he is also extremely mild mannered, and I have rarely ever heard him say anything offensive. I felt like at the very least, the minister could have talked to him about it and told him why it had offended him. Maybe he was just having an off day. But that conversation, coupled with the fact that this minister refused to meet with our disability committee, turned Nik off completely. After several years of trying, first Dwight had given up on the UUs and now Nik was also done.

But I kept going. I had another round in me. The answer to my prayers had dropped in my lap. A group from the Unitarian Universalist Association was looking for a project manager for the (now named) Accessibility and Inclusion Ministry (AIM). It was exactly what we were trying to do at our church, but on a national level. Modeled after the Welcoming Church certification that aided churches to implement steps to make them be more welcoming to congregants in the LGBTQ+ community, it laid out a series of steps for congregations to be more welcoming and accessible to people with disabilities. The team were largely disabled folks, and they were wonderful to work for. I felt like I had real allies who had some power and influence, and this project was exactly what the UUs needed.

My job was to support 7 pilot congregations who had volunteered to go through the program. We were also modifying the program as it went along based of the experiences of these congregations, as well as trying to learn where the challenges were. Within the 7 congregations were some highly committed individuals, both disabled and nondisabled, who wanted to make their churches more accessible and inclusive. I would talk to them on a weekly or biweekly basis and help them through each step of the certification process. They would work on ADA assessments of their programs, church sermons that centered the disability experience, and classes that helped educate about best practices in accessibility and inclusion. The idea was not for each congregation to become perfectly accessible, but to have a plan to constantly prioritize and improve access and inclusion on an ongoing basis.

Some of the congregations had real challenges, like churches on the historical register that could not be easily architecturally modified. Budget was always an issue as well. But often the biggest challenge seemed to me that no one really cared, beyond the committee. Most of the tension was between the committees who wanted to implement the AIM program and the church staff and board of directors. Some challenges were just based on silliness. One church had a large lower and small upper parking lot. The larger lower parking lot had a long flight of outdoor cement steps to get to the church entrance. The smaller upper parking lot had no such barrier to entrance, but it was reserved for the minister and staff. It seemed easy enough to me to change at least some of the upper parking lot into disabled parking. But the ministry refused to do that, because then the entire staff wouldn’t fit up there and they wanted that perk. They chose to close off their church to disabled and elderly people to keep their parking perk. Many times, it isn’t that something can’t be done, it is that it is just not important to anyone.

Another issue that came up often was the issue of disability accommodations being seen as “extra” and “special” such that they were funded by much smaller discretionary “pastoral care” funding rather than incorporated into the operating budget. People with disabilities do not have special needs, their needs are the same as everyone else. Everyone needs accommodations to be able to participate in church life. How narrowly or widelythe church decides to throw out a net to accommodate people has more to do with politics than disability. When disability accommodations are framed as “pastoral care,” it says a lot about what type of people are prioritized as being welcome in the church. If printed orders of service are an operating cost, why would braille or digital orders of service not also be an operating cost? Both are accommodations. If parking lots are operating costs, why would there need to be a special fundraiser to make accessible parking spaces? If PA systems are an operating cost, why aren’t Assistive Listening Devices? Why are accommodations for nondisabled people expected but those for disabled folks are optional and “extra?” Many of them, when integrated from the ground up, don’t even cost any more than more typical accommodations. Budget restraints are difficult everywhere, but people with disabilities should not always be the group that is sacrificed, burdened, and excluded by those budget restraints. Singling out one group for these types of burdens is the very definition of systemic oppression.

Because of some personal, health and job shenanigans in my life at the time, I found myself working four part-time jobs. I needed to lose one. I chose to quit the UUA AIM project, even though I really thought my colleagues were first rate and the project was an important one. But I was just exhausted and disheartened by the UUs. It had been a decade, and those thousand paper cuts, of which only a small fraction are explained here, were starting to really burn. And now I saw them everywhere, on a national level and it was overwhelming. When I quit working for the UUA, I pretty much faded out of the church altogether. It was too tiring, and as a Deafblind person, I had also to advocate for myself in health care, in my children’s education, in my career and in just walking down the street being Deafblind. It was exhausting. Dealing with the UUs was optional; the others often weren’t.

But there was something else. On the whole, the UUs I met were not any better or worse than the general population as far as how they chose to include disabled people. But there were a couple of differences that were hard for me to take. The first is that there is no ADA or other disability civil rights laws to fall back on when dealing with religious organizations. There are some elements of the ADA that churches need to follow in regard to employment, but other than that, they are exempt. This means that all efforts to make their churches welcoming and meet basic legal guidelines for accessibility are voluntary. And it appears that they largely just didn’t want to. Whenever I hear anyone say that no one is against the disabled, and people just don’ t know any better and are confused about the ADA, I think of the UUs. The UUs could have voluntarily done a lot to include disabled folks, had a lot of resources and help to learn how, and simply chose not to.

The other thing that is different about the UUs than the general population is the defensiveness and hypocrisy that I saw over and over again. Once I wrote about my confusion about the UU church in a blog post titled, “I Think I Am an Alien.” Somehow, it got to the minister. I was just about to have my twins dedicated in a UU church service when he wrote to me asking how I could want to have my kids dedicated if I hated the church so much. But I never hated the church. I felt like the church hated me and people like me and I didn’t know how to change it. I broke down and cried, I was so confused. When I tried to make things work for me, I was met with such defensiveness and derision that I wasn’t grateful enough for the little things someone might have already done for me. I just didn’t understand how to “be” in the church, nor how to take seriouslywhat they proclaimed. This is the church that believes in the inherent dignity and worth of each person. This is the church that promotes justice, equality and interdependence. This is the church that promotes acceptance of one another. To see these principles over and over, and yet to feel like there is no place for you in this church hurts. To have worked so hard to try to help the church become welcoming and to be cast off as unimportant hurts. It hurts a lot.

There are a lot of nice, good people in the UU church. As I write this, I imagine that maybe some people reading knew me in the church and were even nice to me and tried to include me and my family. And some really did and I appreciate them. There may be others who may remember me and my family a bit and think that they didn’t try very hard to know me, or didn’t really think about me at all. And I get that and that is ok, too. We have busy lives; we can’t know everyone and help everyone. I’m certainly not the center of the universe. Some may be reading and might be thinking, “I had no idea anything like this happened in my church.” And here is where we might find the crux of the problem.

When I think back on my ten years of UU experiences at multiple different congregations and levels of leadership, I have both good and bad memories. Again, there are a lot of good people in the church. But as I try to find the running theme through what I experienced and what many others with disabilities experienced, the common thread seems to beleadership failures. People didn’t know about my issues because they were never told, nor did they see any action taken by leadership to mitigate them. Time and time again, on all levels, congregants, both disabled and nondisabled tried to improve things in big and small ways, but when they went to leadership, it fell through. I can only theorize about why this might be the case.

The only thing I can come up with is this story I remember from early on in my UU experience. We had a service where the minister answered anonymous questions that people had submitted to a box the week before. He picked out a question and read it to himself and sighed. The congregation laughed. I wondered what difficult question this could be? It turned out that it was my question. I had asked why there were not more racial minorities and disabled folks in the congregation or UU at large and what could be done to be more inclusive? He paused a minute and then answered.

“This is up to you,” he said. “There is nothing leaders can do about it without you all. It has to come from you.” And he shoved the question away and picked another one.

In a democratic organization of associations like the UUA, individuals do have a lot of responsibility for what happens within. And it does take everyone to do the work of change and to make an organization more inclusive of all types of people. But leadership has to lead. In all of my work within the UU organizations, I always had individual supporters. I had Sara Cloe, and Rev. Patti Pomerantz was a great supporter in her all-too-brief temporary tenure at one of my churches, as were many individual congregants. People wished us well when we tried to have the Disability Committee and the AIM project. Individuals offered support. But often, it stopped with leadership. We were cast aside by the leadership who were often “too busy” for people with disabilities and the budget was “too tight” to touch. Leaders are put in these positions by voters to lead and to see the big picture and help set priorities, organize and direct action and set a standard. It is hard to reach the correct balance of being directed by constituents and over-directing them. It isn’t always going to be perfect. But when a concerted effort needs to happen to effect change, leaders need to stand up and set the standard. It feels to me like in the UU organizations; the balance was always off. The leaders only reacted to what they felt was the hot social issue at the time. Disability inclusion was never a hot issue to them.

It has been several years since I effectively ended my participation with the church. I hope that perhaps changes for the better have been made in those years. But I was disheartened to find out that my former AIM project, which I had such high hopes for, has ended its certification program after only four congregations became certified after a decade of work. I still feel that there are a lot of well-meaning people in the church who do want to see congregational life that is more welcoming and inclusive of people with disabilities and other minorities.But they have not been able to effectively organize for more immediate action because they do not appear to have much support from their leaders. One thing that attracted me to the UUs and that I also enjoyed while there was this notion that everyone is choosing to be here, everyone has come together to do good, to be a good person, to feel good and help others feel good. That is very powerful and can be a huge motivation for change. But only if the need to be seen as good doesn’t become a barrier to actually doing good works.

This reminds me of one more “gut punch” story I will share. Once, a very nice woman from church helped me out when I was in a bind by babysitting my children for an afternoon. A few days later, I was at the church for an RE meeting and I saw her in a pastoral care committee meeting. I stopped in and said hi to the women there and thanked her again for babysitting for me. I told her that my kids enjoyed their time with her, and that my son had drawn her a picture, and I would bring it in for her on Sunday. Another woman in the group said, “Aw, that’s what happens when they get too attached.” They all laughed and went on to talk about how they have to be careful when they help “those people” and set boundaries, so “they” don’t have unrealistic expectations and depend on pastoral care too much. I froze; the wind seemed to leave my lungs as I listened to them talk about me and my family, along with others who might have received pastoral care in the third person right in front of me. I had not known I was a “project” for them. I thought my family and I had just made a new friend and someday, we would of course return the favor back to her like friends do. I felt like I would never be seen as a fellow congregant who had gifts to contribute. It felt like my only role for them was to be needy so they could feel like they had done good deeds. I felt very much “othered” and I vowed that I would never seek help from the church for anything anymore.

There are many disabled people out there that are willing to help, even willing to lead the way. They have the skills and knowledge to not only help to make congregations more accessible but have gifts to offer in every aspect of UU life. Some are teachers, accountants, computer programmers, tech folks, et cetera, that have material skills that can assist congregations. Others will be counselors and spiritual leaders. Instead of being fearful of what we will take from you, let us also give to you. When we are ignored and we spend all of our time trying to knock down the barriers preventing us from joining you, all of Unitarian Universalism missed out on a rich and vibrant community of people.

It’s all there for you if you will just unlock the doors.